1. From Greece to America

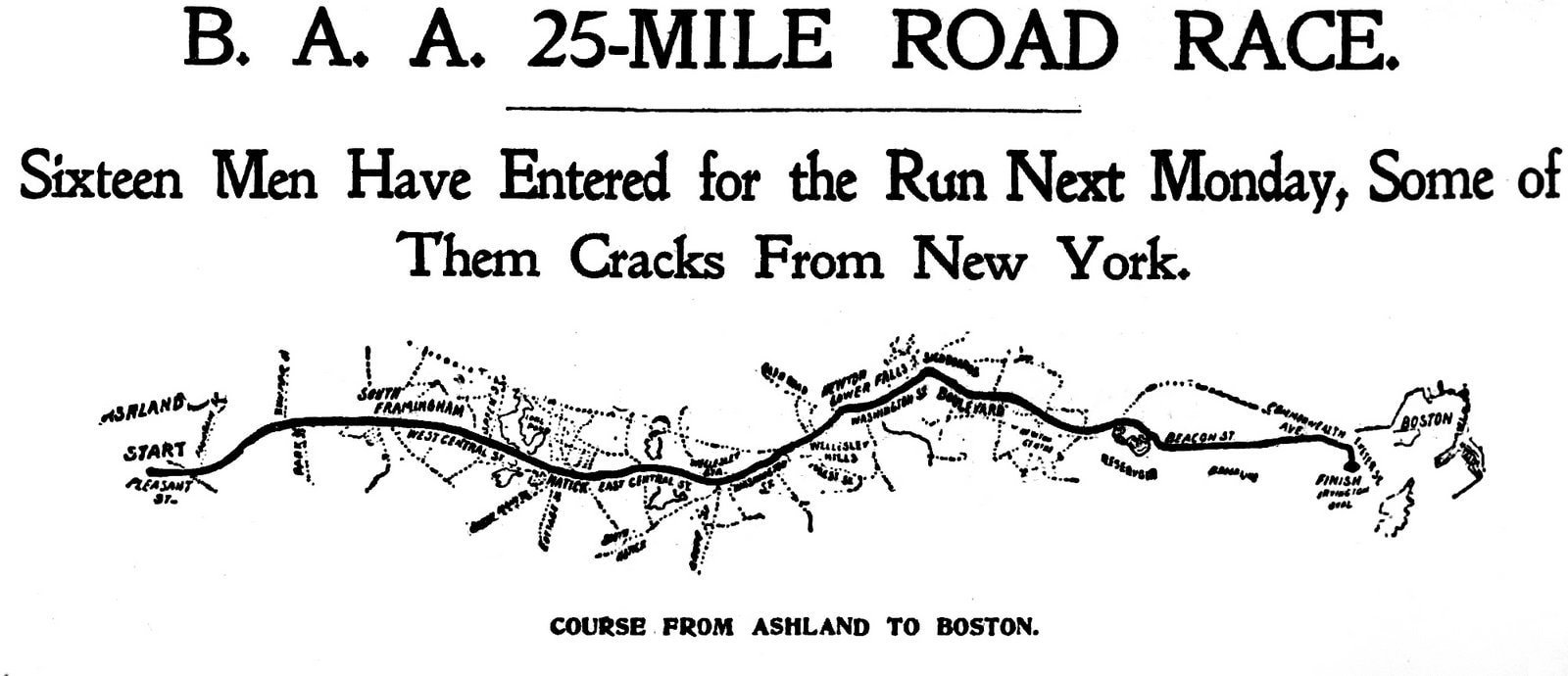

Originally founded in 1897, after the first modern Olympics were held the year before, the Boston Marathon was first run with only 15 competitors. It has since transformed into one of the longest running and most storied events of its kind in the world. At first the course was 24.5 miles, shorter than the 42.195 kilometre or 26 miles and 385 yard distance of the modern marathon.

The course was updated in 1929 in line with Olympic standards first introduced in 1908, where the distance for the event was set at 26 miles and 385 yards. The 1908 marathon route came to be that distance due to changes made to the original plan to avoid some cobblestone paths along the way, and to ensure that more spectators got to view the finish of the race within the stadium. Despite legend saying the finish was extended to the royal box within the stadium, the plan was always to have it finish there. In 1921, the International Amateur Athletics Federation decided to keep this as the official marathon distance, likely at the insistence of Percy Fisher who was on the committee that decided on the route for the 1908 event.

Accordingly, the start of the Boston Marathon was moved back to make the course the correct length. Apart from small changes over the years, the route itself changed remarkably little. This includes the topography of the course itself, dropping over 130 metres from the start to the finish at Boston harbour. As anyone who has run the Boston Marathon can attest, the route also features many hills in the latter parts, including the infamous Heartbreak Hill. The name was coined in 1936 by Jerry Mason of the Boston Globe. The heartbreak happened after John Kelly had snatched the lead from Ellison ‘Tarzan’ Brown, patting him on the shoulder in the process. Brown was able to fight back on the hills near the end of the course, and was able to overtake Kelly at the last major rise.

It is found at mile 20 of the course, rising around 91 feet or 28 metres in half-a-mile. Heartbreak Hill is not the only rise during the course, with the first nine miles of downhill running putting an additional strain on the legs of those competing. The Boston Marathon has therefore gained the reputation of being one of the slower events of its kind for both professional and amateur athletes.

2. Not quite the world record

Nonetheless, conditions occasionally conspired to allow for new marathon world records to be set. Sometimes this has been due to course measurement errors, such as between 1951 and 1956. Thanks to road improvements along the route, straightening various bends along the way, it was found to be 1082 metres or 1183 yards short. This explained the sudden flurry of records that occurred during this period.

The errors nullified the world records set during those years, even though technically there was no marathon world record recognised at the time. The Athletics Congress (TAC), now known as USA Track & Field, decided as the national governing body to officially recognise such records for the first time in 1983. Their decision tied into the efforts of the National Running Data Center (NRDC), which had close ties to officialdom, who in 1982 had started their own program to validate courses on which American records had been set. In 1983, organisers arranged for the course to be remeasured.

David Katz and Bill Noel were selected for the job. Both were heavily involved in the growing discipline of course measurement. Katz would go on to join the team that measured the marathon course for the 1984 Olympics, and also help remeasure the ‘Five Boroughs’ New York City Marathon course that was ultimately found short. It was part of the birth of modern course measurement as we know it today, and you can read more about those efforts here.

As for the Boston Marathon, the pair went to work in March, and used the same exacting standards they had applied to other courses. Mapping the shortest possible route through the various twists and turns of the course, they got their result. The course was approximately one metre short, well within the tolerances set by the NRDC.

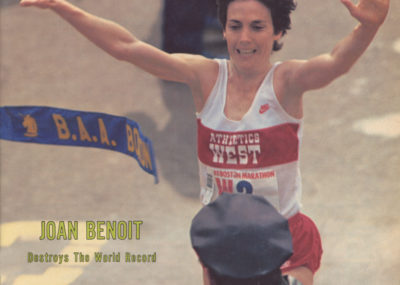

With the accuracy of the course established, organisers could still hold their heads high. Later that year, Joan Benoit shaved off more than three minutes from the women’s marathon world record, winning the event in 2:22:43. Conditions were perfect, cool and overcast with tailwinds in the early stages of the course. Such was her early pace that she had initially been in track to break 2:16, having crossed the halfway point in 1:08:23. Nike would have doubtless been pleased that it was the Lady Terra T/C racing flats that were on her feet.

It was not the first or last such act of athletic heroism. Alberto Salazar famously won the event in dramatic fashion in 1982, collapsing after skipping all drink stations in his effort to beat the opposition. His time was 2:08:52, the fastest time of the year and the second fastest ever over the marathon distance at the time. His shoes were the Nike Skylon Racer, available only to Nike athletes, that had also brought him to victory at the 1981 New York City Marathon. Literally metres behind him was Dick Beardsley, who finished in 2:08:53. A book about their battle was written in 2006, titled Duel in the Sun.

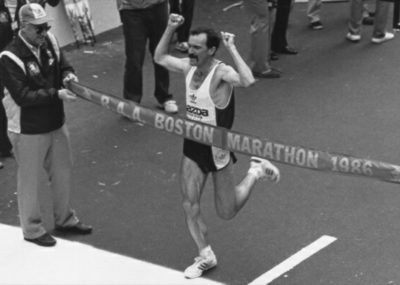

There was also Rob De Castella in 1986, whose 2:07:51 victory was the quickest that year and was then the third fastest marathon of all-time. De Castella had written checkpoint times on his hand so he knew whether he was on track to beat 2:10 or 2:08. His slowest five kilometres of the race was still completed in 15 minutes and 31 seconds, set between the 30th and 35th kilometres that included Heartbreak Hill. Having long worn Adidas products, De Castella was sporting the Marathon Competition 85 that was also worn by fellow running legend Grete Waitz during the same period.

3. New rules

Then in 1990 the International Association of Athletics Federations, now known as World Athletics, introduced Rule 260. This stipulated two new restrictions on marathon courses. First, marathon records could not be set on courses that dropped more than one metre per kilometre. Second, marathon records could not be set on courses with less than 21.1 kilometres between the start and finish. The Boston Marathon overall dropped by an average of 3.3 metres each kilometre.

The reason behind the distance between the start and finish was to prevent favourable tailwinds aiding competitors. For the Boston Marathon course, this was a very real possibility. These changes were reflected by TAC guidance in 1991 as Rule 185.5. There was considerable discussion at the time whether the unique nature of the course cancelled out any such potential advantage. Several experts came forward with mathematical modelling considering this point, and most came back with the conclusion that the downhill portions were not equalised by the notorious hills.

Bob Baumel, one of the team who had measured the 1984 Olympic course, used mathematical analysis to determine how great the effect might be. He found that even with the infamous hills, the overall drop of the Boston Marathon would be equivalent to shortening the standard marathon course by anywhere from 394 to 606 metres.

Then there was the response by Leonard Luchner, who was on the board for the Boston Athletics Association and the Association of International Marathons and Distance Races. He used analysis of the science behind marathon running and countered that the course put strains on athletes unique to the distance, including the timing of the final hills. It goes to show how complex it was to compare the Boston Marathon to flatter courses such as the Rotterdam or Berlin Marathons.

Based on calculations from Ken Young, the founder of the NRDC and later the independent Association of Road Racing Statisticians (ARRS), the Boston Marathon course usually results in elite athletes finishing approximately 172.3 seconds slower compared with their time at the Berlin Marathon on which so many world records have been set. By that logic, Eliud Kipchoge’s world record of 2:01:39 at the 2018 running would have translated to approximately 2:04:31 in Boston. Still incredibly quick, but not the marathon world record.

The closest the Boston Marathon came to the marathon world record in the immediate aftermath of the rule change was in 1994, when Cosmas Ndeti won in 2:07:15, only 25 seconds behind the world record at the time set by Belayneh Densamo in 1988. On his feet were the Nike Air Skylon T/C, the snatch of orange on the outsole giving away the otherwise mostly white shoe. Behind Ndeti was Andrés Espinosa, who was only moments behind him and came second in 2:07:19. Conditions were similar to those that had given rise to such quick times previously, including favourable tail winds.

| Embed from Getty Images | Embed from Getty Images |

It was all the more remarkable in that he was the first winner to run the Boston Marathon with a negative split. Ndeti ran the first half of the race in 1:05 and the second half in 1:02:15. The race also featured an incredible performance by Uta Pippig, whose victory in 2:21:45 made her the third fastest women ever over the distance and only 29 seconds away from the world record at the time set by Ingrid Kristiansen. Pippig had actually decided to slow down for the last four miles, the world record having been a real possibility until that point. Adidas was also able to share some time in the spotlight, Pippig wearing what appears to be the lightweight Torsion Advance model.

4. Enter Geoffrey Mutai

While debate would continue, the marathon world record was broken multiple times by men and women on courses much flatter than in Boston. Then, at the 2011 event, cool temperatures and tail winds of 15-20 miles an hour greeted competitors. Amongst them were Geoffrey Mutai and Moses Mosop. The pair made the race their own, duelling each other across the pavements of the city. There were no pacers to guide them, but it was unnecessary.

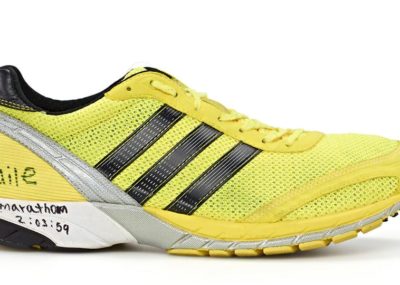

Crossing the finish line, Mutai shaved nearly one minute off the marathon world record by winning in 2:03:02. He was wearing the same Adidas AdiZero Adios racing flats that Haile Gebrselassie had worn to set the world record at the 2008 Berlin Marathon. Close behind him was Mosop, finishing second in 2:03:06. Mutai had without question had secured the course record, but World Athletics announced that he was ineligible for the marathon world record.

Despite lobbying by organisers of the Boston Marathon to have his performance recognised officially as the marathon world record, their efforts were unsuccessful. Because of the nature of the course, the ARRS also does not recognise either Mutai’s achievement or earlier world records set at the Boston Marathon. This of course does not lessen those achievements, nor the event in which they were set.

Amby Burfoot, winner of the 1968 Boston Marathon, observed that the course is capable of freak results with ideal weather and because of such variables should not be eligible for world record consideration. Burfoot also observed that no other marathon comes close to the glorious history of the Boston Marathon. The course has stayed approximately the same for over one hundred years, so it is extremely unlikely changes will be made to comply with World Athletics.

Only the Athens Classic Marathon can claim more history amongst such events. The course is based on modern interpretations of the legend of Pheidippides, who had run from Marathon to Athens in ancient times to report Greek victory against Persia at the Battle of Marathon. After announcing the victory, he collapsed and later died. The course was also used in part for the first modern Olympic marathon in 1896, which as noted above was the inspiration for the Boston Marathon, and again in 2004. Just like its American offspring, the course is notoriously challenging.

Given the nature of marathons, where so many variables can affect the performance of competitors on the day, there is the possibility that another exceptional time will be set at the Boston Marathon. It is however far more likely that courses like the Berlin Marathon will continue to host the marathon world record, although marathon racing has always retained the ability to surprise.

References

http://www.rrtc.net/Pete_Riegel_Archive.html

https://www.runnersworld.com/runners-stories/a20861716/the-endless-toil-of-the-big-data-guy/

https://www.runnersworld.com/races-places/a20783312/is-the-boston-marathons-heartbreak-hill-as-bad-as-they-say/

https://www.runnersworld.com/training/a20829401/apr-20-in-praise-of-the-boston-marathon-course-but-not-for-world-records/

https://www.boston.com/sports/boston-marathon/2017/04/14/why-a-world-record-set-in-the-boston-marathon-wouldnt-officially-count

https://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/19/sports/19marathon.html

https://www.podiumrunner.com/events/should-the-boston-marathon-be-record-legal/

https://runningmagazine.ca/sections/runs-races/boston-marathon-actually-fast-course/

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0184024

https://www.baa.org/races/boston-marathon/history

https://www.thevintagenews.com/2018/04/12/boston-marathon-in-1897/

https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/sports/1986/04/22/de-castella-kristiansen-win-at-boston-marathon/789ad5c5-9f27-465b-9bd9-34b2532cd318/

https://www.nytimes.com/1994/10/30/sports/marathon-ndeti-s-words-to-race-by-run-seldom-but-win-often.html

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1994-04-19-sp-47642-story.html

https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-1995-04-18-1995108100-story.html

https://arrs.run/TB_Mara.htm

https://www.depop.com/products/alexszostek-vintage-og-1994-adidas/

https://www.wired.com/story/how-the-boston-marathon-messes-with-runners-to-slow-them-down/

http://archive.boston.com/marathon/history/1957.shtml

https://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/sdut-boston-wants-mutais-20302-to-be-world-record-2011apr19-story.html

https://www.boston.com/sports/boston-marathon/2019/04/03/boston-marathon-heartbreak-hill-origin/

https://www.runnersworld.com/races-places/a20844024/why-was-the-1983-boston-marathon-so-deep/

https://mobile.twitter.com/deadstockutopia/status/896088358258065408

https://clickamericana.com/topics/culture-and-lifestyle/sports/recap-of-the-first-boston-marathon-1897

https://www.shoesyourvintage.com/product/vintage-1980-nike-lady-terra-tc/

https://trackandfieldnews.com/a-history-of-track-field-news-covers/

https://mobile.twitter.com/deadstockutopia/status/896088358258065408

https://www.runnerstribe.com/len-johnson-articles/on-what-planet-is-this-not-possible-a-column-by-len-johnson/

https://en.paperblog.com/the-42nd-clarence-demar-marathon-nh-2391578/

https://www.defunkd.com/blog/2008/12/10/nike-air-skylon-tc-1993/

https://www.defynewyork.com/2011/10/27/nike-air-skylon-tc-1995/

https://www.historyextra.com/period/ancient-greece/pheidippides-marathon-runner-battle-athens-persia-sparta/

http://isoh.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/177.pdf

http://www.ianridpath.com/polymarathon/history.html

http://www.racingpast.ca/bob-phillips.php?id=25

https://www.instagram.com/p/CcWG5hXpT3Y/